AI adoption in Australian pharmaceutical operations is accelerating—from clinical trial recruitment to pharmacovigilance automation. However, AI privacy in pharmaceutical Australia now poses structural risks fundamentally different from those in traditional IT deployments. Teams deploying AI without documented privacy controls face direct regulatory exposure under reformed legislation.

AI amplifies the scale, reuse, inference, and exposure of personal data in ways that static databases never could. Australian law classifies health data as “sensitive information,” demanding heightened protection. Privacy failures now carry enhanced regulatory penalties and Notifiable Data Breach (NDB) obligations. Additionally, from 10 June 2025, individuals gain a dedicated statutory tort for serious invasions of privacy under the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024. These reforms have effectively collapsed the gap between innovation and liability.

Given these changes, pharmaceutical teams exploring AI face a different question. The focus has shifted from “can we use AI?” to “can we defend how we used it?”

How AI Privacy Pharmaceutical Australia Affects Every Function

AI applications span the pharmaceutical value chain. Clinical trial teams use AI for patient recruitment and eligibility screening. Pharmacovigilance teams automate case intake, coding, and signal detection. Real-world evidence teams analyse secondary data with AI. Digital health teams integrate AI-assisted diagnostics. Meanwhile, internal teams use summarisation and drafting tools for regulatory submissions.

Each application creates privacy implications. Personal data lifecycles extend beyond original consent purposes. AI inference generates new personal information from existing records, potentially creating re-identification risks from ostensibly de-identified datasets. Human oversight erodes when AI outputs bypass medical review. Furthermore, vendor-driven data flows introduce third-party processing that organisations may not fully understand or control.

Compounding this, the OAIC guidance states that where AI generates or infers personal information, that activity is treated as a ‘collection’ under the Privacy Act (APP 3). Separately, AI outputs containing personal information must be handled in accordance with the APPs. This means organisations now bear compliance obligations for information generated by AI as well as for data entered by humans.

The Australian Privacy Law Foundation: What Every AI System Must Satisfy

The Privacy Act 1988 and its 13 Australian Privacy Principles establish the legal foundation for AI deployments handling personal information. Five APPs carry particular weight for AI privacy, pharmaceutical Australia compliance. Consequently, pharmaceutical leaders must now proactively embed privacy protections into each phase of AI adoption and operation, ensuring legal compliance and patient trust.

| APP | Requirement | AI Implication |

|---|---|---|

APP 3 | Collection must be lawful, fair, reasonably necessary | Training data collection requires defined, specific purposes |

APP 6 | Use and disclosure limited to primary purpose | AI reuse for secondary purposes requires legal basis |

APP 8 | Cross-border disclosure accountability | Cloud AI with overseas processing triggers disclosure obligations |

APP 10 | Data quality and accuracy | AI outputs must meet accuracy and fitness-for-purpose standards |

APP 11 | Reasonable security steps | Technical controls must match threat environment |

No AI exemption exists under privacy law. The “reasonably necessary” standard under APP 3 creates a high bar when organisations collect extensive datasets for AI training without specific, defined purposes. AI outputs can themselves constitute personal information—making organisations responsible for synthetic data generated through inference.

What Changed Recently—Why 2025-2026 Is a Turning Point

The Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 fundamentally reshaped the risk calculus for AI deployments. Three reforms demand immediate attention.

First, the statutory tort for serious invasion of privacy, effective June 2025, creates direct civil liability. Individuals can now sue for privacy breaches without demonstrating financial harm. The Federal Court’s October 2025 decision in OAIC v Australian Clinical Labs—imposing penalties of $5.8 million—demonstrates the regulatory willingness to pursue substantial enforcement.

Second, automated decision-making transparency obligations take effect from 10 December 2026. Organisations using AI to make decisions that significantly affect individuals must disclose this in their privacy policies. Clinical trial eligibility screening, pharmacovigilance case prioritisation, and safety signal evaluation all fall within scope.

Third, a proposed ‘fair and reasonable’ test is expected to introduce principles-based assessment of whether data collection and use meets acceptable standards—even with consent. While not yet law, regulators already use this framing to set expectations for high-risk AI deployments.

Enhanced civil penalties can now reach $50 million, three times the benefit obtained, or 30% of adjusted turnover.

AI, Cybersecurity and APP 11: The Technical Privacy Expectation

APP 11 requires “reasonable steps” to protect personal information from misuse, loss, and unauthorised access. For AI systems, “reasonable” increasingly ties to cybersecurity maturity benchmarks.

The Australian Signals Directorate’s Essential Eight is widely regarded as the baseline cybersecurity mitigation strategy in Australia. For entities processing health data through AI systems, APP 11 ‘reasonable steps’ will increasingly be assessed against at least Essential Eight-equivalent controls.

Clinical trial management systems, pharmacovigilance databases, and safety reporting platforms represent high-value targets for cyber actors. Legacy systems integrated with AI overlays create specific exposure—older architectures often lack the logging, auditability, and breach-detection capabilities that modern threat environments demand.

Privacy by Design for AI in Pharma: Where to Start

Effective AI privacy governance begins with the right question. Not “what can AI do?” but “what data, what decision, what regulator, what harm?”

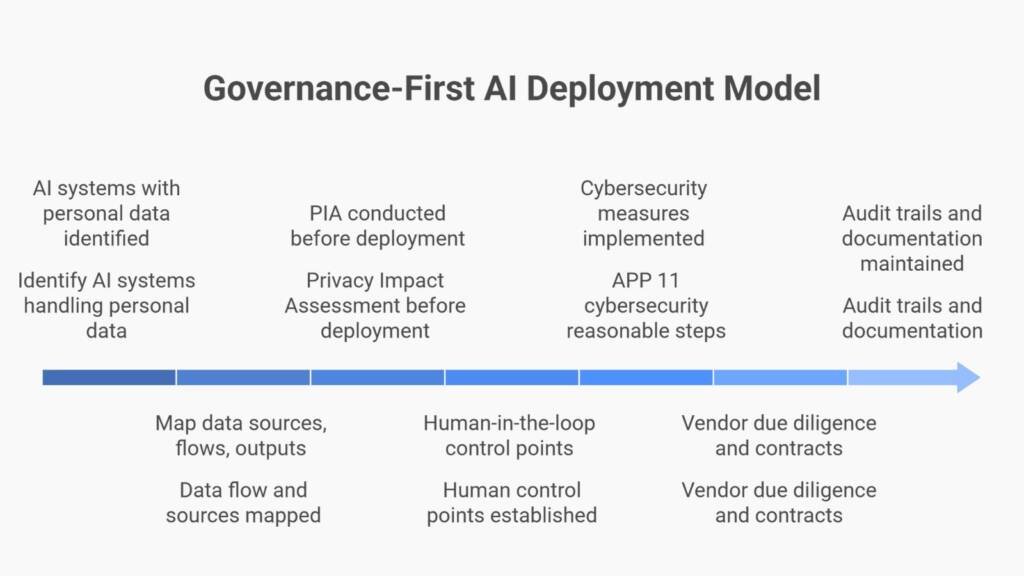

Foundational steps include:

- Identify all AI systems touching personal or health data

- Map data sources, flows, outputs, and retention points

- Clarify decision impact on individuals

- Determine whether AI influences regulated outcomes (safety decisions, eligibility determinations, regulatory submissions)

Essential artefacts for defensible AI deployment:

✓ Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) completed before deployment

✓ Data classification and provenance documentation

✓ Defined human-in-the-loop (HITL) control points

✓ Retention schedules and deletion procedures

✓ Audit trail demonstrating compliance

The OAIC requires PIAs for high privacy risk activities undertaken by government agencies, and strongly recommends them for any entity deploying AI systems that make decisions with legal or similarly significant effects on individuals

Where Privacy Breaks Down in Real AI Use Cases

Privacy failures in pharmaceutical AI typically occur in four domains.

Clinical trials: Consent forms drafted for traditional trial conduct often fail to cover AI reuse of participant data. Digital twin models generate inferred personal information that participants never provided. Training datasets reflecting historical biases produce AI outputs with subgroup performance disparities.

Pharmacovigilance: Automated case intake pulls personal information from unstructured sources without explicit collection notices. AI narrative generation creates synthetic case descriptions that may inadvertently expose identifiable details. Vendor platforms process cases through cloud infrastructure where data flows remain opaque.

Real-world and secondary data: Dataset linkage creates re-identification risks from supposedly anonymised records. Purpose creep extends data use beyond original collection scope. Cross-border analytics trigger APP 8 obligations that organisations often fail to recognise.

Internal AI tools: Staff using consumer-grade AI tools expose employee and customer data to third-party training datasets. Shadow AI—unapproved tools deployed for convenience—bypasses governance controls entirely. Enterprise versus consumer licensing distinctions determine whether data remains protected or enters vendor training pipelines.

Scenario: A pharmaceutical sponsor deploys an AI tool for literature surveillance in pharmacovigilance. The tool processes published case reports to flag potential signals. However, the vendor’s terms permit customer data to train future model versions. The sponsor’s clinical data—including identifiable patient details from literature cases—enters the vendor’s training dataset without APP 8 cross-border disclosures or data processing agreements. When the OAIC investigates, the sponsor lacks documentation demonstrating awareness of this data flow.

Ethical Expectations and Public Trust in AI-Driven Health Decisions

Australia’s eight AI Ethics Principles—covering human-centred values, fairness, contestability, accountability, and transparency—inform regulatory interpretation even though they remain voluntary. The principles shape how the OAIC assesses whether AI practices meet “fair and reasonable” standards.

For pharmaceutical organisations, ethical alignment carries practical weight. If AI use cannot be explained to a patient, defended to a regulator, and justified to a court, it lacks defensibility. The 2023 Australian Community Attitudes to Privacy Survey found that 96% want conditions in place before AI is used to make decisions affecting them, and 71% want to be told when AI is used.

Public trust erodes when AI operates as a “black box.” Partner confidence depends on demonstrable governance. Reputational risk now compounds regulatory exposure.

Practical Privacy Controls for AI-Enabled Pharma Organisations

Governance controls:

- Maintain an AI register with documented ownership and accountability

- Track automated decision-making for December 2026 disclosure obligations

- Align privacy, quality, and IT policies so AI governance operates consistently

Technical controls:

- Deploy enterprise-grade AI only— consumer tools lack data processing agreements and contractual protections that address Australian Privacy Act obligations.

- Implement data loss prevention to detect sensitive information transmission

- Configure access controls, role-based permissions, and comprehensive audit logging

Operational controls:

- Conduct vendor due diligence including AI-specific questionnaires

- Apply change control to AI model updates and retraining events

- Integrate breach response with NDB scheme notification timelines (30-day assessment, prompt notification)

The Upside: What Organisations Gain by Getting Privacy Right

Privacy governance enables AI scale rather than blocking it. Organisations with documented controls experience faster regulator engagement, fewer remediation cycles, and stronger partner confidence.

Strategic benefits include:

- Regulatory discussions proceed from demonstrated capability rather than gap closure

- AI deployments expand without accumulating compliance debt

- Litigation exposure reduces through documented due diligence

- Partner organisations—sponsors, CROs, vendors—trust your data handling practices

Privacy is not an obstacle to AI adoption. It is the foundation that makes adoption sustainable, defensible, and scalable.

Conclusion: AI Enablement Without Privacy Debt

AI in pharmaceutical operations arrives inevitably. Privacy failure remains optional.

Australian regulators now expect evidence, not intent. The statutory tort, enhanced penalties, and ADM transparency obligations have shifted the compliance landscape. Organisations deploying AI without documented privacy controls accumulate liability that compounds with each additional use case.

Governance-first AI adoption—starting with PIAs, data classification, human oversight, and audit trails—now represents the fastest path forward. Organisations that embed privacy by design today will capture AI’s efficiency benefits while maintaining inspection readiness and patient trust.

The question for pharmaceutical teams centres not on whether to use AI. It centres on whether your AI privacy approach in Australia is defensible when regulators ask for evidence.

FAQ Section

Does the Privacy Act apply to AI systems that only process de-identified data?

Yes, if there is a reasonable likelihood of re-identification. AI inference can combine de-identified records with external data sources to re-identify individuals. The OAIC considers information “personal information” if re-identification is reasonably likely—making organisations responsible for AI outputs that enable re-identification even from supposedly anonymised datasets.

When does the automated decision-making transparency requirement take effect?

The ADM transparency obligation becomes mandatory from 10 December 2026. Organisations using AI to make decisions significantly affecting individuals’ rights or interests must disclose this in their privacy policies. Pharmaceutical teams should begin mapping AI systems now to ensure compliance readiness and identify high-risk deployments requiring enhanced controls.

What is the “fair and reasonable” test and how does it affect AI?

The “fair and reasonable” test is a proposed future reform (not yet law as of early 2026) that would require organisations to demonstrate their data collection and use practices are objectively fair and reasonable from the perspective of a reasonable person—even when consent has been obtained. This recognises that consent alone may be insufficient where power imbalances exist. While not yet enacted, regulators already use this framing to set expectations for high-risk AI deployments in clinical trials and pharmacovigilance. When implemented, it will require organisations to justify AI data practices against community standards, not just legal formalities.

Are there different privacy requirements for enterprise versus consumer AI tools?

Yes, substantially. Enterprise AI platforms typically offer data processing agreements, data residency controls, and contractual prohibitions on using customer data for model training, with terms that address Australian Privacy Act obligations. Consumer tools—including free or personal accounts of ChatGPT, Copilot, or Gemini—generally permit vendor use of input data for model training, creating APP 6 (purpose limitation) and APP 8 (cross-border disclosure) exposures. Australian organisations remain accountable for ensuring any AI tool meets Privacy Act requirements, regardless of vendor certifications.

How does APP 11 “reasonable steps” apply to AI systems specifically?

APP 11 requires technical security proportionate to data sensitivity and threat environment. For AI systems processing health data, “reasonable steps” now ties to benchmarks like the Essential Eight. Organisations must demonstrate encryption, access controls, audit logging, patch management, and breach detection capabilities aligned with the sensitivity of data processed by AI.

What documentation should pharmaceutical organisations prepare for AI privacy compliance?

Essential documentation includes updated privacy policies and Privacy Impact Assessments conducted before AI deployment, data classification and provenance records, documented human-in-the-loop control points, vendor due diligence records including AI-specific questionnaires, change control logs for model updates, and audit trails demonstrating compliance with APPs. This documentation package supports both regulatory inspection and litigation defence.

Can we rely on vendor certifications to demonstrate AI privacy compliance?

Vendor certifications (SOC 2, ISO 27001) provide evidence of vendor security controls but do not transfer compliance responsibility. Australian organisations remain accountable for ensuring AI deployments meet Privacy Act requirements. Certifications support vendor due diligence but must be supplemented with contractual protections, data flow mapping, and ongoing monitoring of vendor practices.

Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It is intended to support general understanding of regulatory concepts and good practice and does not constitute legal, regulatory, or professional advice.

Regulatory requirements, inspection expectations, and system obligations may vary based on jurisdiction, study design, technology, and organisational context. As such, the information presented here should not be relied upon as a substitute for project-specific assessment, validation, or regulatory decision-making.

For guidance tailored to your organisation, systems, or clinical programme, we recommend speaking directly with us or engaging another suitably qualified subject matter expert (SME) to assess your specific needs and risk profile.