What Is Artificial Intelligence in Practical Pharmaceutical Terms?

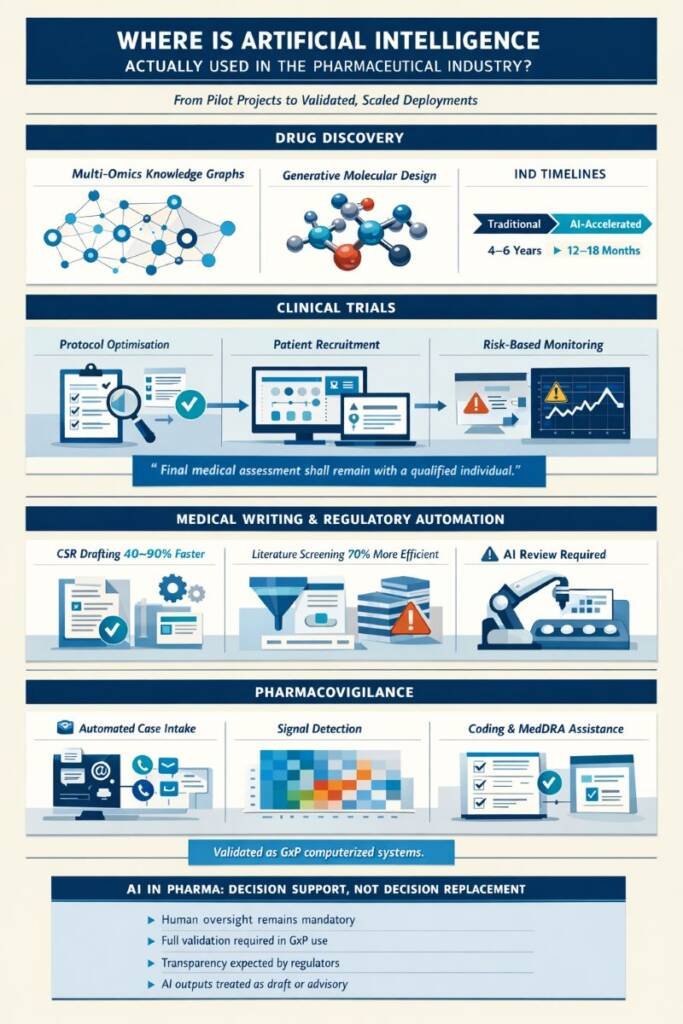

Artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical settings means computer systems that learn patterns from data to support decisions—unlike traditional LIMS, EDC, or MES platforms that follow fixed “if-then” rules you program once and validate statically.

The critical difference: deterministic systems always produce the same output from the same input. AI operates probabilistically, analysing historical data—clinical outcomes, batch parameters, safety reports—to generate predictions with confidence levels, not certainties. That’s both the opportunity (handling data volumes manual processes can’t manage) and the validation challenge (behaviour may shift as models retrain on new data).

The GxP Reality

Traditional Computer System Validation assumes unchanging software. AI breaks that assumption. Your validation approach needs three shifts:

- Initial validation — Assess training data quality, define intended use boundaries, pilot-test in controlled settings

- Continuous validation — Monitor for model drift, re-evaluate against current data, adjust protocols as algorithms evolve

- Risk-based framework — Prioritise validation effort where patient impact is highest

The patient safety principle doesn’t change. The method does. AI doesn’t eliminate human accountability—it augments expertise you already have while creating audit trails you can defend to the TGA.

Why This Distinction Matters for GxP Professionals

In the pharmaceutical industry, AI shifts the paradigm from deterministic (fixed logic) to probabilistic (statistical prediction). This change transforms how we approach compliance:

- The Shift: We are moving from “verifying code” to “continuously assuring performance.”

- The Goal: Aligning with FDA/EMA Computer Software Assurance (CSA) by focusing on risk-based monitoring rather than one-time validation.

How Does Machine Learning Work in Pharmaceutical Applications?

NOTE: ML doesn’t “understand” science; it identifies patterns in data to predict outcomes.

| Type | Process | GxP Example |

|---|---|---|

Supervised | Learns from labeled data (known outcomes). | Pharmacovigilance: Training a model on 50k past reports to automatically triage “serious” vs. “non-serious” cases. |

Unsupervised | Finds hidden clusters in unlabeled data. | Manufacturing: Grouping production sites based on subtle performance trends. |

Critical Note: Models inherit the biases of their training data. If your data lacks pediatric representation, your AI will fail that population. Data quality is your primary safety control.

What About Deep Learning and Its Black Box Challenge?

Deep learning, a specialised subset of machine learning, uses multi-layered artificial neural networks to model complex patterns in large datasets. In pharmaceutical contexts, deep learning excels at analysing medical images (detecting subtle patterns in pathology slides or X-rays), predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences, and processing complex molecular structures for drug discovery.

The trade-off involves explainability. Deep learning models may contain millions of parameters across dozens of layers, making it difficult to explain precisely why a specific prediction was made. Regulators and quality professionals expect to understand AI decision-making logic, especially when it influences product quality or patient safety. Consequently, many organisations deliberately choose simpler, more interpretable models for high-risk applications—even if deep learning might offer marginally better accuracy—because explainability supports regulatory defensibility and audit readiness.

Transitioning from CSV to Computer Software Assurance

The pharmaceutical industry is moving from documentation-heavy Computer System Validation (CSV) toward Computer Software Assurance (CSA), which focuses validation effort on system components with the highest impact on patient safety and product quality. This risk-based approach corresponds better with artificial intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry because:

- Traditional CSV assumes static software behaviour, whereas AI models may be retrained periodically.

- CSA emphasises critical thinking about actual risks rather than exhaustive test scripts

- Validation becomes an ongoing assurance process with continuous monitoring rather than a one-time qualification event.

Organisations implementing AI should adopt lifecycle management approaches that define intended use, assess risks, establish performance acceptance criteria, validate against those criteria, monitor continuously, and manage changes under formal change control—all documented to regulatory standards.

What Are the Major Limitations and Risks to Understand?

Short Answer: Artificial intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry introduces specific risks that require active management: over-automation leading to deskilling and unchallenged acceptance of incorrect outputs, algorithmic bias causing systematically different performance among patient subgroups or operational situations, model drift where performance degrades as real-world data distributions change, data privacy breaches when sensitive information is inadequately protected, and hallucinations where generative AI produces factually false information with high confidence. All these risks make qualified human monitoring a scientific and regulatory requirement, not an optional enhancement.

To address over-automation, implement explicit policies that define the scope of AI decision support and require human review for high-stakes decisions. For algorithmic bias, diversify training datasets and regularly conduct audits to identify and rectify disparities in AI performance. Model drift can be mitigated through continuous performance monitoring and retraining triggered by significant deviations. Strengthen data privacy by enforcing strict access controls and adopting encryption practices to protect sensitive information. Finally, reduce the risk of hallucinations by using AI in conjunction with human oversight, ensuring that any AI-generated outputs are rigorously vetted before acceptance.

The Model Drift Challenge

- A manufacturing deviation prediction model trained on one facility’s equipment may perform poorly after equipment upgrades or when deployed to a different facility.

- A clinical trial recruitment model trained pre-pandemic may fail when patient care patterns shift post-pandemic

- A pharmacovigilance coding model trained on specific products may struggle with new indications or formulations.

The Over-Automation Risk

Over-reliance on artificial intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry, without appropriate checks, can lead to deskilling, as professionals lose critical thinking skills by routinely accepting AI recommendations without independent evaluation. In safety-critical processes, unchallenged AI decisions could pose patient risks and lead to regulatory non-compliance.

Organisations need explicit policies defining:

- Which decisions AI can support versus which require mandatory human review

- How conflicts between human judgment and AI outputs are resolved and documented

- What training do professionals receive to work effectively with AI tools?

- When AI assistance is inappropriate, regardless of technical capability

What Artificial Intelligence Is NOT: Dispelling Common Misconceptions

Artificial intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry is not sentient, conscious, or capable of independent judgment. Current AI systems are sophisticated pattern-matching engines that identify statistical correlations in training data. They do not “understand” biology, pharmacology, or ethics in human terms, and they cannot be held accountable for regulatory decisions.

Common misconceptions that harm implementation:

- “AI will fix our bad data”: AI amplifies both the strengths and weaknesses of the underlying data. Poor data quality produces unreliable models.

- “More complex models are always better”: Simpler, interpretable models are often preferable in GxP contexts because explainability supports regulatory compliance and audit readiness.

- “AI replaces domain experts”: AI augments human skills by managing high-volume, pattern-recognition tasks, allowing experts to focus on complex tasks that require moral judgment and strategic reasoning.

- “One model works everywhere”: AI models are context-dependent. A validated model for cardiology cannot simply be used for oncology without complete retraining and re-validation.

AI Implementation Checklist in GxP

Intended use clearly defined

What specific decision does this AI support, and how will outputs be used?

Risk assessment completed

What patient safety or product quality risks exist if the AI performs incorrectly?

Data quality verified

Does training data meet ALCOA+ principles and represent the intended use population?

Human monitoring established

Who reviews AI outputs, and what authority do they have to override recommendations?

Performance monitoring planned

How will we detect model drift or decline over time?

Validation strategy documented

What performance metrics define acceptable AI behaviour for this context?

Change control defined

How will model updates be evaluated, approved, and implemented?

Vendor oversight implemented

If purchasing AI from vendors, how do we audit their development and quality practices?

Conclusion: A Measured, Competency-Based Approach to AI Adoption

Artificial intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry represents an evolution of analytics and automation that must operate within existing GxP, quality, and regulatory frameworks. Success depends equally on technology capability, data governance maturity, and human expertise.

Pharmaceutical professionals should view AI as advanced decision support requiring validation, monitoring, and oversight comparable to other computerised systems—not as a revolutionary exception to established quality principles. Organisations achieve sustainable value by starting with constrained, high-value use cases where data quality is strong, and AI clearly augments existing workflows: literature screening with human review, risk-based monitoring enhancement, targeted pharmacovigilance triage, or manufacturing process analytics.

The joint FDA-EMA principles, FDA’s credibility framework, and EMA’s draft Annexe 22 provide clear regulatory direction: demonstrate fitness for intended use through risk-based validation; maintain complete traceability; ensure explainability; continuously monitor performance; and mandate qualified human monitoring for critical decisions. These requirements align artificial intelligence in the pharmaceutical industry with patient safety, product quality, and regulatory trust—the foundational principles that must guide all pharmaceutical innovation.

AI in GxP: Essential Questions and Answers

Is artificial intelligence allowed in GxP-regulated pharmaceutical systems?

Yes. AI is allowed in GxP systems as long as it is risk-based validated, embedded in the quality system, maintains data integrity and audit trails, and has qualified human oversight.

Does artificial intelligence need formal validation like other computerized systems?

Yes. AI used in GxP must be formally validated with a risk-based approach that defines intended use, sets acceptance criteria, monitors performance over time, and manages changes under change control.

Can we use generative AI tools to draft regulatory submission documents?

Yes, for draft content only. Generative AI can produce first drafts of CSRs, narratives, and summaries, but qualified experts must fully review, correct, and approve all text before regulatory use.

What’s the difference between predictive and generative AI in pharmaceutical applications?

Predictive AI forecasts outcomes or classifies data to support decisions. Generative AI creates new content—molecules, text, or images—and needs tighter governance due to hallucination and explainability limits.

How do we detect if an AI model’s performance is degrading over time?

Track key performance metrics against validated baselines and monitor input data distributions. Significant drops or data shifts should trigger investigation, retraining, or retirement under change control.

Who is responsible when artificial intelligence makes an incorrect recommendation?

Accountability remains with the qualified human who reviews and acts on the AI output. AI is a decision-support tool, so organizations must define oversight roles, training, and documentation for decisions.

What should we ask AI vendors before purchasing pharmaceutical AI tools?

Ask about intended use, validation evidence, performance-drift monitoring, data-use policies, audit trails, update/change controls, and security and privacy protections for sensitive pharma data.

What documentation do regulators expect for AI systems in GxP environments?

Regulators expect clear intended use, data-flow and architecture descriptions, validation plans and reports, performance metrics, change-control records, and SOPs for AI lifecycle and incident management.

How should we manage data used to train and test pharmaceutical AI models?

Treat training/test data as GxP-relevant: ensure integrity of source systems, document selection criteria, control bias, and apply strong privacy, de-identification, and access controls.

When is AI not appropriate for GxP-regulated pharmaceutical processes?

AI is unsuitable when fully explainable, deterministic behavior is required, data are poor or unstable, or the organization cannot reliably monitor and govern the model over its lifecycle.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – Guiding Principles of Good AI Practice in Drug Development

- European Medicines Agency (EMA) & U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – Guiding Principles of Good AI Practice in Drug Development

- European Commission – EU GMP Annex 11: Computerised Systems

- International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) – GAMP® 5 Guide: A Risk-Based Approach to Compliant GxP Computerized Systems, Second Edition

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – Computer Software Assurance for Production and Quality System Software

Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It is intended to support general understanding of regulatory concepts and good practice and does not constitute legal, regulatory, or professional advice.

Regulatory requirements, inspection expectations, and system obligations may vary based on jurisdiction, study design, technology, and organisational context. As such, the information presented here should not be relied upon as a substitute for project-specific assessment, validation, or regulatory decision-making.

We have no commercial relationship with some of the entities, vendors, or software referenced. Any examples are illustrative only, and usage may vary by organisation and their needs.

For guidance tailored to your organisation, systems, or clinical programme, we recommend speaking directly with us or engaging another suitably qualified subject matter expert (SME) to assess your specific needs and risk profile.